The history of the GDPR

The history of the GDPR

Let us go back in time. The national census meant that, every ten years, there would be a knock on every door in the Netherlands to record the number of people living there. This happened in 1971 as well.

Civil resistance

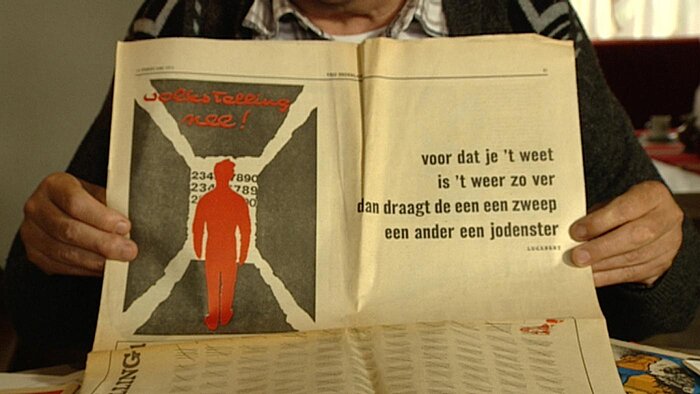

Even before 1971, there was growing resistance from citizens to this method of recording data. But from 1971 onwards, this protest movement came to be led by the ‘Census Vigilance Committee’ (Comité Waakzaamheid Volkstelling) as the above poster by Lucebert illustrates. ‘Critics tended to associate the census with World War II; after all, that was only 25 years ago at the time. The occupying forces made good use of the well-maintained population registers to deport the Jews’ (source: Andere Tijden, Dutch TV programme on history).

Moreover, didn’t the government already have all the data for Dutch residents, for example, via birth records? Last but not the least, there were objections about the fact that the census also recorded information on philosophical beliefs, disabilities, and income. And it turned out that, in practice, an increasing number of people were providing fictitious information to the census authorities because refusal was punishable with a fine of 500 Dutch guilders or imprisonment.

Andere Tijden: De burger in kaart - De Volkstelling in 1971

Watch the broadcast (in Dutch only) below:

National Committee

Around 1970, there was a discussion in society about the powers of the National Security Service (BVD, currently known as the General Intelligence and Security Service (AIVD)) relating to the monitoring of citizens via wiretaps. A bill entitled ‘Further rules for the protection of telephone privacy’ (Nadere regels ter bescherming van het telefoongeheim) debated by the House of Representatives in 1970 focused on the lack of control over the National Security Service (source: Jan Holvast, The 1971 census - report of the first general public discussion on the invasion of privacy (De Volkstelling van 1971 verslag van de eerste brede maatschappelijke discussie over aantasting van privacy). 2013. p. 56.)

The discussion surrounding the 1971 census prompted Minister of Justice Van Agt to establish a National Committee for the protection of privacy in relation to the recording of personal data in 1972. This Koopmans Committee published its findings in the report entitled ‘Privacy and Recording of Personal Data’ (Privacy en Persoonsregistratie) (source: National Committee for the protection of privacy in relation to the recording of personal data. Privacy and Recording of Personal Data. Final report of the National Committee on the protection of privacy in relation to the recording of personal data (Staatscommissie bescherming persoonlijke levenssfeer in verband met persoonsregistraties. Privacy en persoonsregistratie. Eindrapport van de Staatscommissie bescherming persoonlijke levenssfeer in verband met persoonsregistraties). The Hague, 1976).

In this report, the Koopmans Committee sets out ’the legal or other measures desirable for the protection of privacy in connection with the use of automated recording systems for personal data and to what extent it is desirable that these measures should also apply to other records of personal data’ (source: Privacy and Recording of Personal Data, p. 5). The Committee formulated principles for a legal regulation, its main features, and attached a proposal for a legal regulation: a draft bill for a Personal Data Registration Act (Wet op de persoonsregistraties (WPR)).

The Committee summarises the principles of the envisaged regulation as follows (see pp. 28, 29: Privacy and Recording of Personal Data):

- Ensuring that the recording of personal data becomes more transparent through openness and publicity

- Strengthening the legal position of persons whose data are recorded vis-à-vis holders of these personal data records

- Ensuring that the registration and use of personal data is subjected to a more direct level of supervision, in particular by setting restrictive rules and establishing a special supervisory body

The bill was presented to the House of Representatives in 1981, and after a few adjustments, came into effect as the Personal Data Registration Act (WPR) on 1 July 1989 (source: https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0011468/2018-05-01).

Evolution of the law over the years

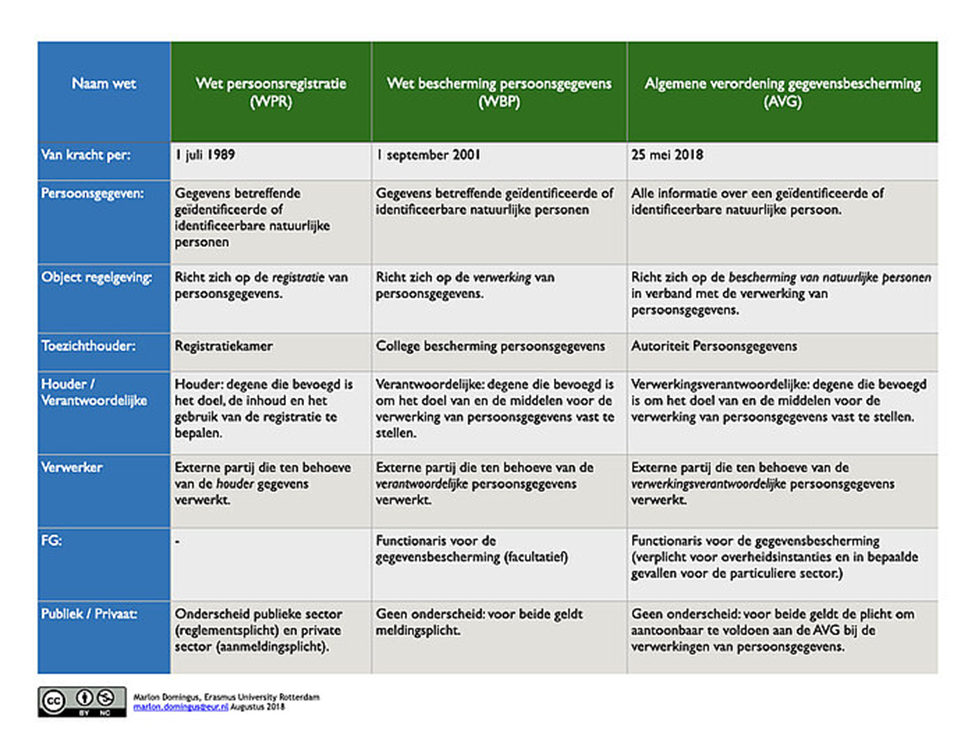

Below is a comparison between the WPR, its successor the WBP, and the successor to that, the GDPR. It is striking to see how little has actually changed in all this time:

Not a new law

So the GDPR is not a completely new law but one with an approximately 50-year-old history. Both the principles and concepts as well as measures such as encryption had been mentioned by the Registration Board (Registratiekamer, the then Dutch DPA) as possible options. For example, the report by G.W. van Blarkom and J.J. Borking (source: Personal Data Protection. Background Studies and Explorations No. 23 (Beveiliging van persoonsgegevens. Achtergrondstudies en Verkenningen 23). Registration Board. 2001 - online: https://www.cs.ru.nl/~jhh/pub/secsem/registratiekamer-av23.pdf) examines the encryption of passwords (p. 44) and the communication of data (p. 45). Similarly, the report (source: Can it be a bit less? About Privacy-Enhancing Technologies 2002 (Mag het een bitje minder zijn? Over Privacy-Enhancing Technologies 2002) - online: https://autoriteitpersoonsgegevens.nl/sites/default/files/downloads/brochures/bro_pet.pdf) of the Data Protection Board (College Bescherming Persoonsgegevens), the successor to the Registration Board, mentions encryption of a patient identification number as an option (p. 18).

A major difference between the GDPR and the earlier laws is that now there is a supervisory authority (the Dutch DPA) which has the power to immediately issue fines (source: https://autoriteitpersoonsgegevens.nl/nl/nieuws/cbp-krijgt-boetebevoegdheid-en-wordt-autoriteit-persoonsgegevens). Since these fines can be as high as 20 million euros or 4% of an organisation’s annual global turnover (source: GDPR Article 83(2.5)), they form a serious disincentive. So, failure to properly protect personal data can suddenly lead to serious financial consequences for organisations.