- Functioning of the GDPR

To fully understand how the GDPR works, it is important to know that the GDPR is a general regulation and a principle-based law.

The GDPR is a general regulation for two reasons:

1. It is drafted in generic terms and only outlines principles on how to deal with personal data. For specific policy areas, there is specific legislation (such as (in Dutch only) the New Intelligence and Security Services Act (Nieuwe Wet op de inlichtingen- en veiligheidsdiensten (WIV)) or the Medical Research (Human Subjects) Act (in Dutch only) (Wet medisch-wetenschappelijk onderzoek met mensen (WMO)). This specific legislation takes precedence over general legislation (such as the GDPR).

2. The GDPR is technology neutral: the legal text does not mention specific technologies or specifications thereof, such as the encryption key length (128, 192 or 256 bits) for data encryption. The possible technical and organisational measures have been discussed earlier in Chapter 4 (Measures).

A principle-based law

Some laws are based on principles and open standards, while other laws have clear objective criteria and are therefore based on closed standards. An example of the latter is the road sign indicating a speed limit of 100 km/hour between 6:00 and 19:00.

Road signs like the one shown above tell you exactly what the speed limit is on a motorway at a particular time. With a principle-based law such as the GDPR, there are no objective criteria, and instead it uses concepts such as:

- Purpose not incompatible with the initial purposes

- A vital interest

- Appropriate safeguards

- A high risk

- Necessary

- Proportional

- Fair

The advantage of open standards is that the legislator does not have to make rules for every concrete situation or for every technical development (reduces the regulatory burden). The GDPR is essentially concerned with the defined purposes (goal-based regulation). See also Council of State Annual Report 2018: Open standards and legal certainty(in Dutch only). A disadvantage of open standards, as also mentioned in this Annual Report, is the legal uncertainty:

Open standards involve a risk of disagreement arising about their interpretation. If the legislator does not provide sufficient guidance, the courts will ultimately have to decide on the interpretation of a standard.

Based on the formulated principles, a researcher will always have to examine which measures are necessary to safeguard, to the best extent possible, the defined purposes for the protection of personal data within a research project. For this, policy rules (formerly: guidelines) laid down by the national supervisory authority, the Dutch DPA, give further meaning to the open standards, see an overview of this here (in Dutch only).

Court rulings also provide further clarification, for example, see here (in Dutch only), where the court in preliminary relief proceedings has ruled that a university may use online surveillance software (proctoring) during examinations and where it confirms that the university in question has complied with all the rules and principles of the GDPR.

Finally, the Court of Justice of the European Union, which is the highest authority, further clarifies the GDPR. For example, on 16 July 2020, in its famous Schrems II ruling, the Court went so far as to declare a decision of the European Commission invalid, i.e. the so-called adequacy decision of the US based on the Privacy Shield.

Case law therefore plays an important role in principle-based legislation with open standards because these standards and certain contexts gradually become clearer based on the entire body of court judgements.

Lex generalis and lex specialis

In addition to the fact that the GDPR is a principle-based law, it is important to be aware of the relationship between a general regulation (a lex generalis such as the GDPR) and sector-specific laws (lex specialis). If, in a given case, a sector-specific law (lex specialis) as well as the GDPR (a general regulation, lex generalis) are applicable, the principle of lex specialis derogat legi generali shall apply, i.e. this principle of speciality gives priority to specific legislation over general legislation. For example, the UAVG is specifically a national law and hence takes precedence over the GDPR.

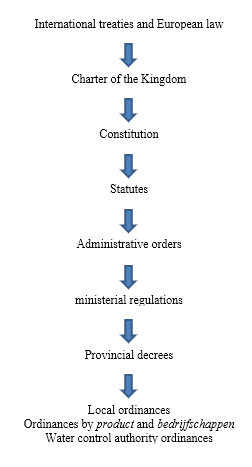

But in case of conflicts between laws, another principle applies, i.e. lex superior derogat legi inferiori, which defines the hierarchy between higher and lower legislation. The higher legislation issued by the highest legislator takes precedence. This means that if there is any conflict between specific and general laws, the general legislation (GDPR) will still override the specific legislation (UAVG). As it happens, specific legislation usually contains more specific provisions. Only if there is a conflict as a result of this, will the higher legislation prevail. Although this does occur, it is more of an exception. See also the image displayed earlier which clearly shows the hierarchy between the different laws.

Additional provisions and exceptions for scientific researchThe GDPR explicitly states that Member States have a degree of freedom in further interpreting certain aspects of the GDPR. An example of this is GDPR Article 9 (Processing of special categories of personal data), paragraph 2, subparagraph j. Here the GDPR states that Member States can make additional provisions: The processing is necessary for archiving purposes in the public interest, scientific or historical research purposes or statistical purposes in accordance with Article 89(1) based on Union or Member State law which shall be proportionate to the aim pursued, respect the essence of the right to data protection and provide for suitable and specific measures to safeguard the fundamental rights and the interests of the data subject. Our national implementation legislation, the UAVG, includes additional provisions for the purpose of scientific research. In this context, the UAVG states the following more specifically in Article 24: Exceptions for scientific or historical research purposes or statistical purposes In view of Article 9(2)(j) of the Regulation, the prohibition on the processing of special categories of personal data does not apply if: a. the processing is necessary for scientific or historical research purposes or statistical purposes in accordance with Article 89(1) of the Regulation; b. the research, referred to in subparagraph a, serves a public interest; c. seeking explicit consent proves impossible or involves a disproportionate effort; and d. the implementation provides for sufficient safeguards ensuring that the privacy of the data subject is not disproportionately affected.

How should this be interpreted? We have seen that in this respect the UAVG takes precedence (lex specialis) over the general rule from the GDPR. UAVG Article 22 (in Dutch only) specifies in greater detail that, in the Netherlands, special categories of personal data may only be processed lawfully for research purposes if it can be demonstrated that requesting research participants for their consent ‘proves impossible or involves a disproportionate effort’. Here the UAVG actually prescribes the ‘comply or explain’ approach as a basic principle: consent should be explicitly requested from research participants if special categories of personal data are processed in research or it should be explained why this is not possible or not possible with a proportionate amount of effort. In some places, the GDPR clearly indicates that national implementation legislation may further interpret a GDPR obligation as seen, for example, in the case of the BSN (national identification number) (GDPR Article 87): ‘Member States may further determine the specific conditions for the processing of a national identification number or any other identifier of general application.’ |